I have eagerly awaited the final season of Game of Thrones, and its strange blend of fictive medieval Britain, supernatural monsters and pornography. Over the seasons the plot has gained speed and focus while the pornography has vanished and – incredible as it seems – we can also detect that George R.R. Martin’s fantastic story has a message. Perhaps we can explain its enormous success by considering how, at a subconscious, dreamlike level, it deals with humanity’s most profound problem.

I want to believe that my interpretation is more than a pathetic attempt to legitimise all those hours of passive TV-watching. Just as the great anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was able to expose central problems of specific Amerindian peoples by analysing their myths, we can analyse our own tales in order to discern the contradictions and apparently unsolvable dilemmas that torment our subconscious.

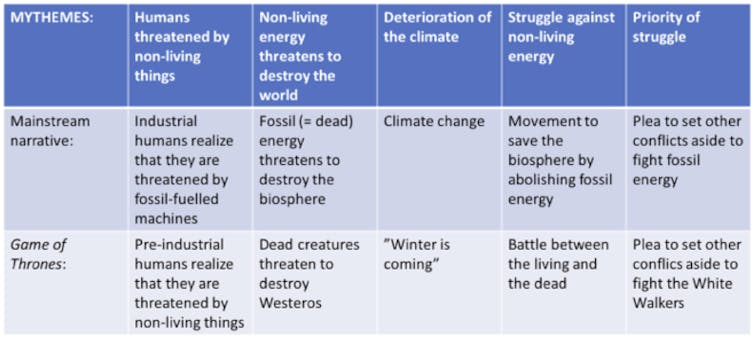

What Lévi-Strauss called “mythemes” are abstractions of central elements of stories – the basic themes which express their essential messages. Using his method for dissecting myths, we can unearth submerged meanings in fantasy and science fiction. And these dreamy worlds tell us more about ourselves than we generally realise.

Two decades later the roles were reversed. The final scene in “Avatar” instead shows an evil male capitalist, dressed in similar technological armour, being defeated by a benevolent Nature. The entire ecosystem of the planet Pandora is mobilised in the battle against the human exploiters. Now it is the machines, rather than the monsters, who come from another planet. In this story, technology loses the battle against nature. Only by stopping the machine can nature survive.

Fossil energy is at war with life itself

A similar analysis reveals the real threat against the warring medieval kingdoms in Martin’s imaginary continent of Westeros. The White Walkers’ army of dead beings threatening to destroy the world of humans, accompanied by ongoing climate change (“winter is coming”), is an allegorical representation of fossil fuels. Today, the energy that propels our technological civilisation derives from countless billions of dead organisms whose extinguished sparks have been buried in the Earth’s crust. The metaphor is not at all far-fetched: in both cases, fossil energy is at war with life itself.

Fear of the Night King’s murderous corpses could of course be interpreted simply as the existential fear of death which might unite all people. But the connection between the dead army and climate change is sufficiently distinct to make a more political allegory convincing. The forces animating the dead beings threaten to lead to the collapse of civilisation as a whole, beyond the lives of individual humans. As smuggler-turned-knight Davos Seaworth points out to Daenerys: “If we don’t put aside our enmities and band together we will die. And then it doesn’t matter whose skeleton sits on the Iron Throne.”

Although the intuition that the approaching White Walkers’ winter could be seen as a metaphor for climate change may be fairly widespread among followers of Game of Thrones, the literal identification of dead (fossil) energy as a lethal threat to humanity appears to have escaped most analyses. The army of zombies evokes modern society’s stock of machines animated by long-dead inorganic energy in the form of coal, oil or gas. Like pre-modern people confronted with such technical contraptions, the inhabitants of Westeros are shocked by the magical capacity of dead objects to move and to wage war on the living.

George R.R. Martin’s message is that the continuous human competition for power must be set aside in a joint effort to defeat the threat from the army of the dead. The message from Game of Thrones appears familiar and urgent at a time when humanity is subconsciously struggling with its paradoxical ability to sweep the climate crisis under the carpet while preoccupying itself with everything else. As in a dream, we try to make sense of the contradiction between our awareness of the approaching catastrophe and our remarkable capacity to ignore it. Dreams and fantasies prompt us to reflect on matters that we suppress. In that sense, Game of Thrones is a tale for our times.